The above painting shows a glomerulus containing capillary loop fibrin thrombi, an arteriole with onion-skinning, and acute tubular injury, findings that can be seen in thrombotic microangiopathy. Morphologic findings of thrombotic microangiopathy that can be seen on a renal biopsy include arteriolar or capillary loop fibrin or platelet thrombi, red blood cell fragmentation within glomerular capillary loops or within arteries, mesangiolysis, endothelial cell swelling, glomerular basement membrane duplication, mucoid intimal edema of arteries, and a myointimal proliferation surrounding arterioles (onion-skinning like reaction).

Thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) has a wide clinical differential diagnosis, which can have substantial morphologic overlap on a kidney biopsy. Clinicopathologic correlation is always required in these cases to arrive at a potential etiology. Potential etiologies include accelerated hypertension, scleroderma renal crisis, certain drugs, infections (such as Shiga-toxin induced hemolytic uremic syndrome), antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, malignancy, disorders of complement regulation (atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome), and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (Brocklebank et al, 2018).

A thrombotic microangiopathy can affect the glomerular compartment, the vascular compartment, or often both. When microangiopathic changes are restricted to the vascular compartment, the findings can usually be attributed to accelerated hypertension, scleroderma renal crisis, and anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome. Vascular involvement can also lead to tissue ischemia and/or infarction of the renal parenchyma.

Some medications can cause this disease. Inhibitors of VEGF-A, used to prevent tumor angiogenesis and reduce tumor growth, can cause a TMA that shows hyaline deposition within vascular lesions within glomeruli (Eremina et al, 2008). Gemicitabine, used in the treatment of bladder cancer and other solid tumors, can induce a chronic active TMA (Humphreys et al, 2004). A chronic active thrombotic microangiopathy will show a membranoproliferative pattern of glomerular injury on a biopsy.

A chronic active TMA can be distinguished from other causes of a membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis due to the lack of immune complex deposition and evidence of endothelial injury (subendothelial widening and endothelial cell swelling). In addition to gemcitabine, myeloproliferative neoplasms, graft versus host disease, radiation exposure, and hemoglobinopathies (including sickle cell nephropathy) can show this pattern of injury. Remote pre-eclampsia is another consideration for patients with a history of renal dysfunction in pregnancy.

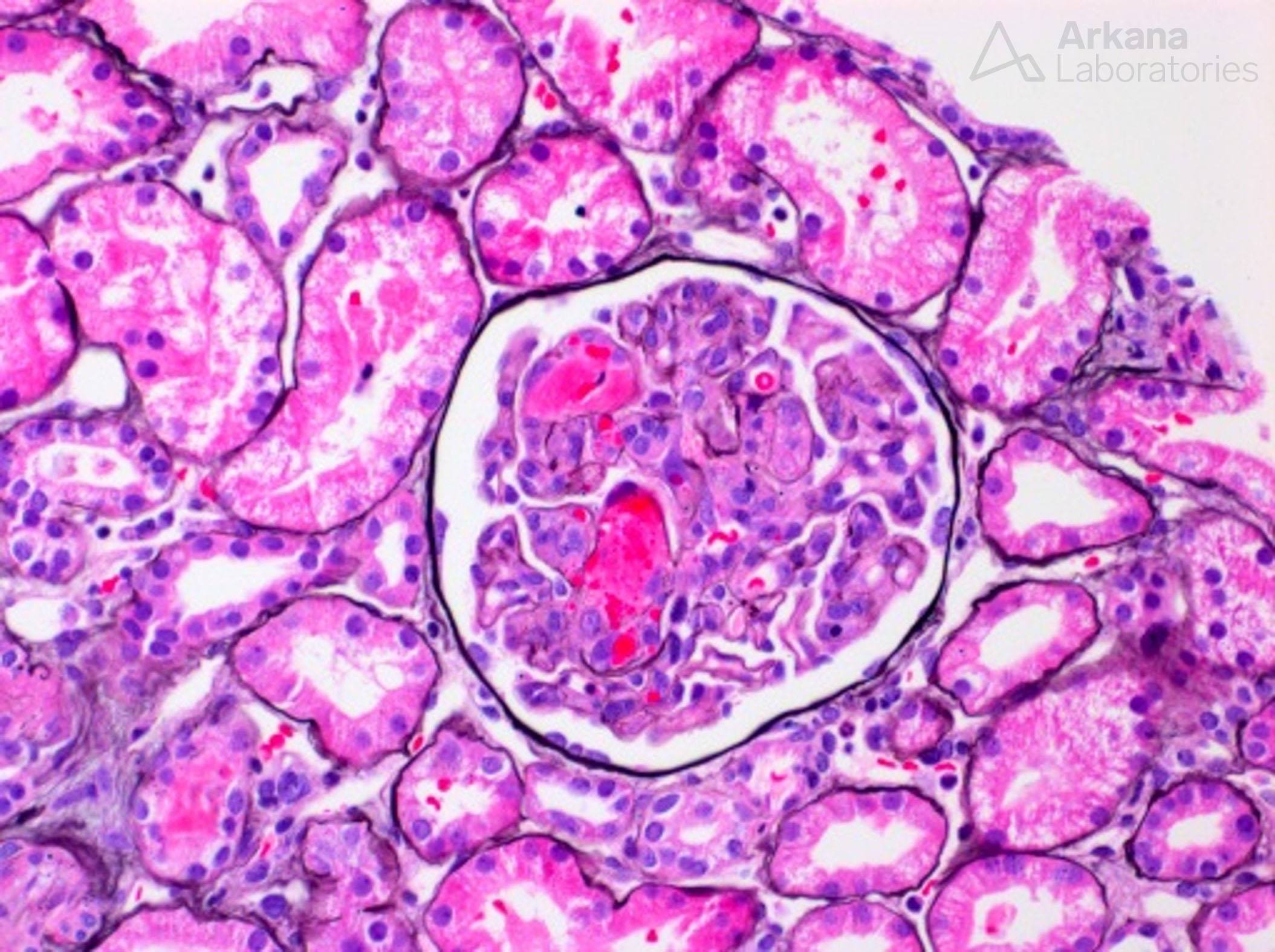

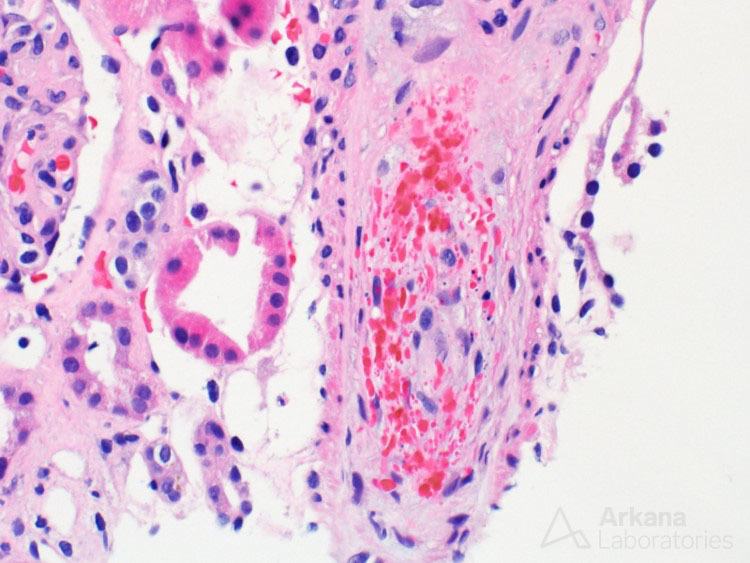

In the absence of an insulting medication, malignancy, infection, ADAMTS13 deficiency (TTP), or malignant hypertension, a work up for deregulation of the alternative pathway of complement can be considered to evaluate for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (a-HUS). Atypical HUS can be due to development of autoantibodies against regulators of the alternative complement pathway (anti-factor H antibodies or anti-C3 nephritic factor) or due to genetic mutations in complement components (Larsen et al, 2018). Some renal biopsy images from a case of thrombotic microangiopathy are shown below.

Glomerulus with capillary loop fibrin thrombi from a case of thrombotic microangiopathy.

An artery with endothelial cell swelling, luminal occlusion, and red blood cell fragmentation from a case of thrombotic microangiopathy.

References:

Brocklebank V et al. Thrombotic Microangiopathy and the Kidney. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018 Feb 7;13(2):300-317.

Eremina, Vera, et al. VEGF Inhibition and Renal Thrombotic Microangiopathy. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:1129-1136.

Humphreys BD, Sharman JP, et al. Gemcitabine-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Cancer. 2004 June 15;100(12):2664-70.

Larsen CP et al. Genetic testing of complement and coagulation pathways in patients with severe hypertension and renal microangiopathy. Mod Pathol. 2018 Mar;31(3):488-494.

Quick note: This post is to be used for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical or health advice. Each person should consult their own doctor with respect to matters referenced. Arkana Laboratories assumes no liability for actions taken in reliance upon the information contained herein.